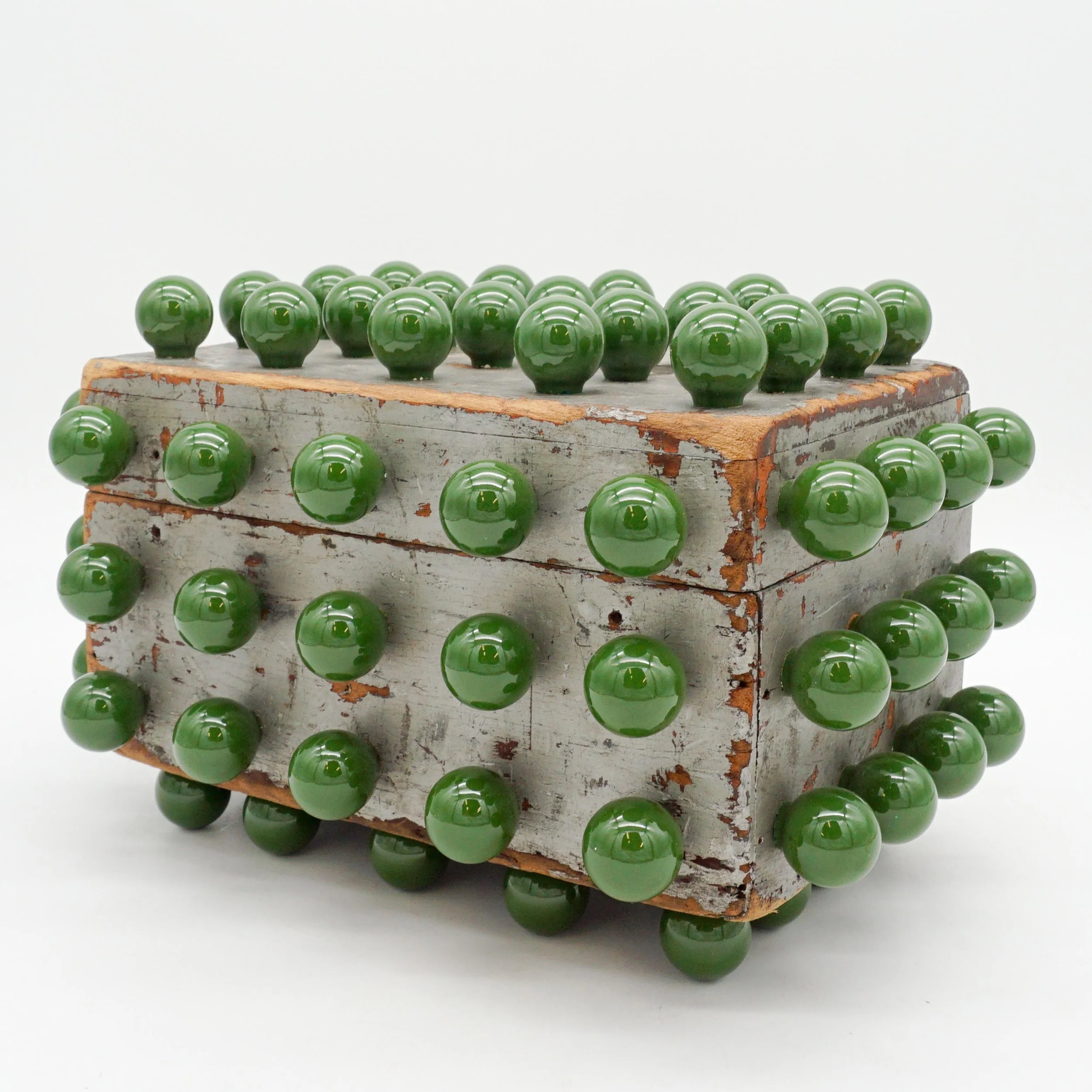

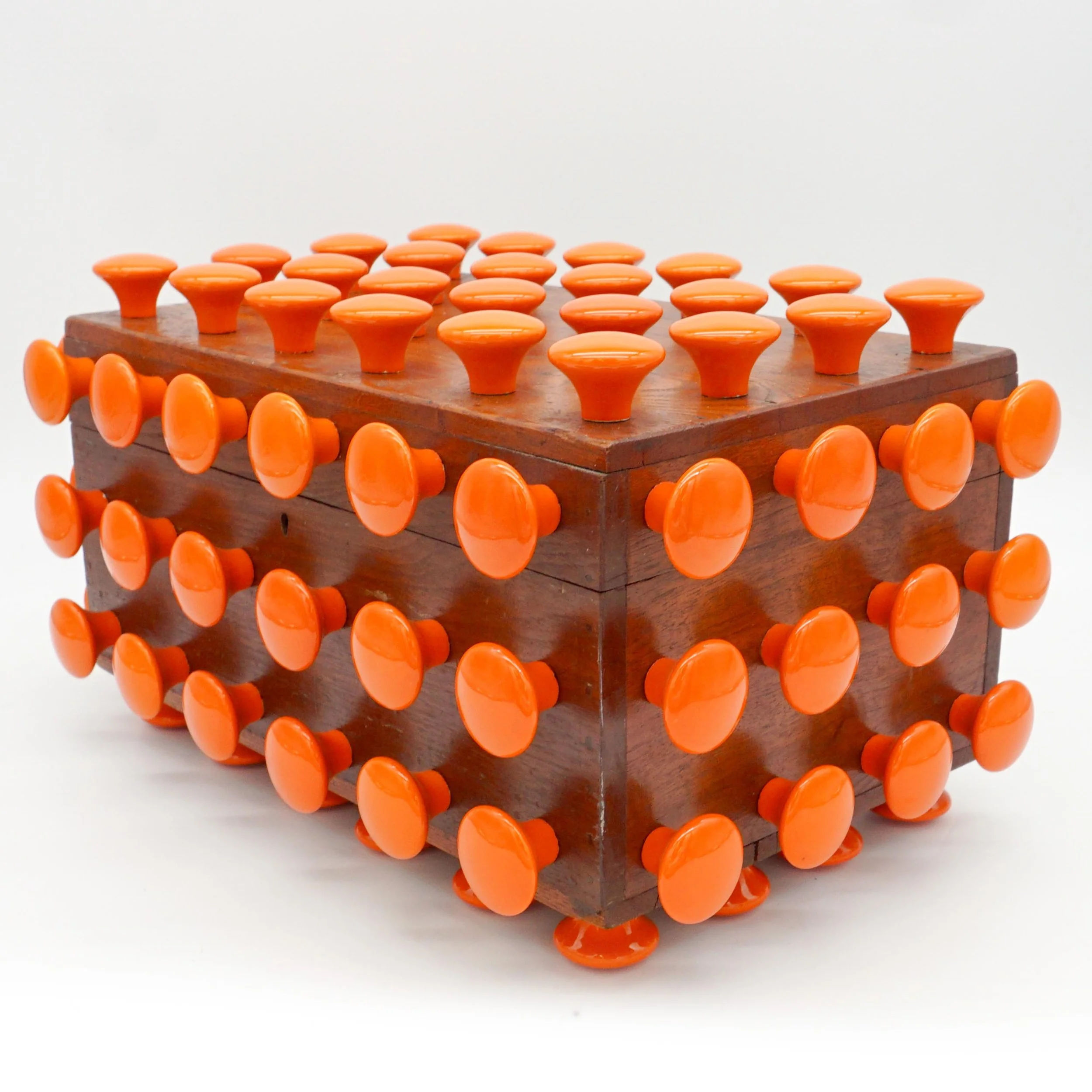

Knob Box No. 11

Contact the gallery to purchase this work.

Adam Raiford Wilson

Bio

Adam Raiford Wilson is a 26-year-old multimedia artist based in Madison, originally from Benton, Arkansas. His work centers on the use (and misuse) of art materials to highlight the low-quality garbage that defines modern consumer culture. Wilson advocates for consumption habits that support skilled craftspeople and rejects the mass production of digestible corporate home decor.

From a distance, much of Wilson’s work could be mistaken for stains, spills, or actual garbage. In 2023, a TikTok in which he showed a series of pressure-washed paintings on cotton paper went viral for all the wrong reasons. Over five thousand comments, primarily negative, hated the concept that time could be spent attempting to replicate the texture and color of trash. This reaction encouraged him to unpack why viewers seemed insulted by the concept and to push those same processes further.

ARWIL combines traditional art materials such as oil, acrylic, and graphite with nontraditional application techniques.

After moving from Arkansas four years ago, ARWIL has settled in Madison with his husband, Logan, and their two cats. Since then, his work has been featured in coffee shops and retail spaces around the city. This spring, ARWIL completed a 3-month artist residency in Beaumont-des-Pertuis, France. Working in such a remote and ancient village provided a unique opportunity to focus exclusively on his art and to draw inspiration from the textures around him. Works from this residency were exhibited at The Bounty in Madison, where he will be undertaking his next residency in 2025.

Artist Statement

Over the last year, I have been exploring the concept of semantic satiation through found-object sculptures. I have found that when a mundane object (door knobs, beads, car keys, etc.) is removed from its expected context and used in large quantities, the original object becomes almost unrecognizable. The repetition of something common and often overlooked rips expectations from the viewer, prompting them to investigate the sculpture and attempt to dissect its components.

At the same time, this now unrecognizable object takes on a sacred or religious aura. Questions prompted might include: Why was this made? For whom was it created? What is its purpose? I attempt to assemble these sculptures in such a way that the most logical conclusion is that these are religious objects. Icons that someone, anyone, might pray to. Yet, even when the viewer accepts the sculpture as sacred, there is no historical context as to whom it might be significant to. Ideally, the sculpture creates questions but leaves a space for the viewer to imagine answers.